What is Eelgrass?

By Phil Colarusso

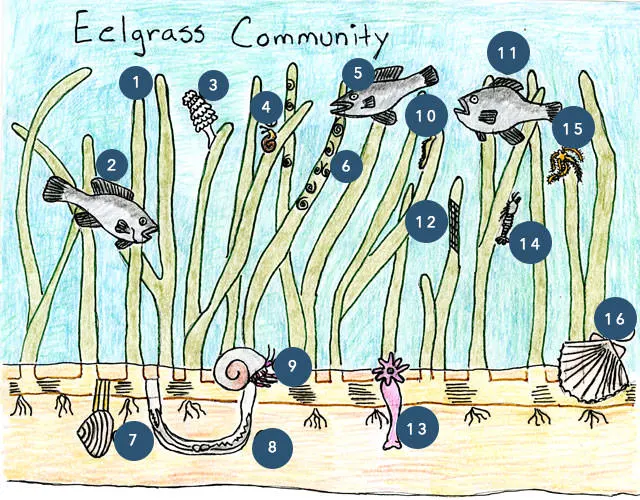

1. Eelgrass; 2. Common mummichog; 3. Moon jelly (polypoid stage); 4. Common periwinkle; 5. Striped killifish; 6. Coiled tube worm; 7. Soft-shell clam; 8. Parchment tube worm; 9. Hermit Crab; 10. Nudibranch; 11. Sheepshead minnow; 12. Encrusting bryozoan; 13. Burrowing anemone; 14. Sand Shrimp; 15. Short-spined brittle star; 16. Bay scallop

Massachusetts is home to 2 species of seagrasses eelgrass (Zostera marina) and shoalgrass (Rupia maritima). Of those 2 species, eelgrass is by far the most common, comprising over 98% of the seagrass in the state.

Eelgrass is a rooted plant that is found in brackish to saline waters. It is a plant that requires a large amount of light for survival, so it is generally restricted to shallow water. Along the Massachusetts coast, eelgrass can be found in clear water to depths of 25 feet mean low water, but is more commonly restricted to 15 feet mean low water or less. It prefers quiescent protected areas, with silty/sandy sediments.

Seagrasses serve numerous important ecological functions. They are critical nursery, refuge and foraging habitat for a wide range of fish and invertebrates. Phil Colarusso of EPA, Mark Chandler of the New England Aquarium and Robert Buchsbaum of Mass Audubon collected fish from eelgrass meadows in Nahant, Gloucester and Hingham. They found 34 different species of fish utilizing this habitat from small sticklebacks to juvenile sand tiger sharks. In southern Massachusetts, bay scallops and blue crabs are 2 commercially important invertebrate species that rely heavily on healthy seagrass meadows.

Seagrasses, along with salt marshes and mangroves, are important buffers to climate change and ocean acidification. These habitats sequester large quantities of carbon primarily in the sediments below the vegetation. Most of the carbon found in the sediments in seagrass meadows originates outside of the meadow. Phytoplankton and particulate organic matter settle out of the water column due to the presence of the leaves in the meadow. The organic layers also known as peat, can build up over time and the carbon contained within them can be stored for hundreds of years. Loss of the overlying vegetation would allow for the release of all that stored material back into the ocean and atmosphere. Scientists from EPA, MIT SeaGrant and Boston University have been sampling eelgrass meadows around New England to quantify how much carbon is being stored, how old the carbon is and where it comes from. Nahant has served as one of the sample stations for this work.

Seagrasses are important primary producers that help fuel the base of the food chain. Eelgrass predominantly enters the food chain through detritus, though it is directly consumed by brant geese, black ducks, Canada geese and some small crustaceans and gastropods. Seagrasses reduce erosion. Their extensive root and rhizome system keep sediments in place and their leaves serve to dampen waves reducing erosion to adjacent shorelines.

Eelgrass abundance in Massachusetts has generally reflected a slow decline in many areas. Eelgrass acreage in Nahant/Lynn area has declined significantly since 2012. The exact cause(s) of this decline are not clear. Grazing by geese in the winter, winter storms, green crabs and or declines in water clarity may all be contributing factors to this demise.

Eelgrass restoration is feasible, but it tends to be very labor intensive, expensive and has traditionally had a poor track record of success. Researchers at the Northeastern Marine Science Center are examining if increasing genetic diversity among transplanted shoots might lead to better restoration success.